-

-

Stood in the minus 20 degree cold of the Icelandic winter, Helen Booth didn’t have long to make a sketch of the dramatic landscape around her. In these freezing temperatures frostbite would set in in less than thirty minutes. And, without gloves, her hands were so cold that she could only really work for a few minutes, but these extremes also helped to focus her mind and emotions. Working quickly with a charcoal stick, she drew thin lines that skidded and

slid across the surface of the paper. She sensed the landscape with frozen fingers; lines

looping, darting, dashing, tumbling, leaving slithers of luminous darkness on the whiteness of the page, tantalising suggestions of forms hidden in the snow, rocks felt underfoot or far off mountains glimpsed receding into the distance. In this blurring of micro and macro, she synthesised the complexity of this ancient landscape into an abbreviated shorthand of

evocative marks.

Booth’s work is a product of both the far north and the landscape surrounding her Welsh studio. Her restrained palette of white, blue, black and grey evokes the hues of snow and ice, glaciers and slate. We see the mist rising above hot geysers, we are bathed in the freezing, cleansing waters of Iceland’s majestic waterfalls, find ourselves enveloped in the perpetual dark of the Arctic winter waiting for the coming of light, and shelter in the shadowy depths of gentle Welsh valleys. These subtle colours envelop us in a symphony of silence, occasionally interrupted by a momentary burst of yellow, pink and green that bring with them the warmth of sunlight, flesh and the promise of new growth and spring.

And emerging from this encounter, this meeting of the physical and metaphysical, comes grey: Blue grey, steel grey, slate grey, the colour of earth and clouds and cold seas - the colour of incarnation. In these greys we glimpse the world we both see and feel, the uniting of its visible, physical form and it’s invisible, metaphysical presence.

Ridges of pigment, left by the tangled swirl of a brush stroke, trace Booth’s hand dragging form into space, making visible, not what she has seen, but her remembered sensations as she stood in a blizzard or gazed out over the Welsh or Icelandic landscape. Sand, chalk, shredded paper and the rough textured weave of canvas also snag Booth’s fluid washes of colour and light with their materiality. From a distance, these minute particles of landscape and visual memory disappear into the harmonious solidity of the picture surface, but when we look more closely, we begin to notice them, they hold us in their gravitational field and before we know it, the thin washes of paint around them seem to evaporate, vanishing into an insubstantial blur - a gaseous cloud of intangible colour.

Recently, Booth has started to pierce the surface of her work, breaking its physical tension as she roughly squeegees, brushes and drags paint across the canvas. Through these real holes she might draw torn pieces of canvas, or she might leave them open and empty, allowing our eyes to be pulled through the canvas into the space beyond and behind. But more often, she encourages our gaze to play in the space of colour, to move constantly between surface and depth. She teases with a dot, a full stop that arrests our gaze with its presence, a shape,

defined by an edge. But if we ignore the outer edge and gaze into its centre, the circle

becomes the end of a line, extending in front of us, inviting us in. We find our gaze drawn into the limitless space of the implicit line that lies ahead. Focusing on the line, the shape

disappears and what had once been a form becomes formless, like ice melting into water, before it evaporates into steam.

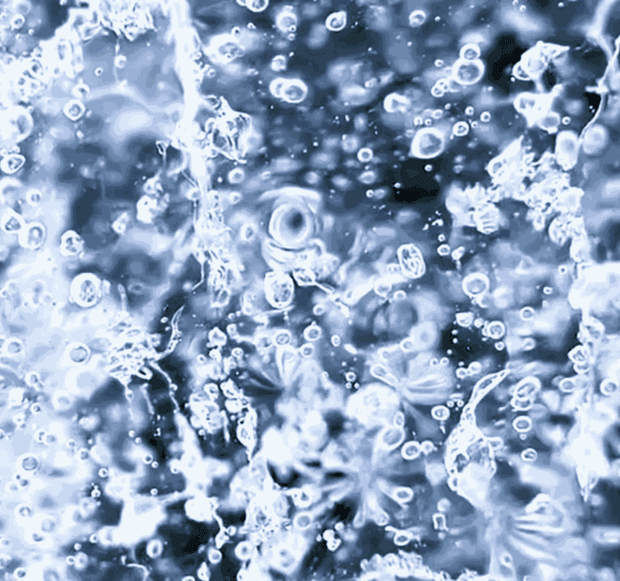

Booth fills the space around these circles with the percussive rhythm of quick dashes and rapid dabs drawn in ink and paint. Gently rocking crescents extend like intersecting waves towards the horizon, darting in hesitant murmurations coalescing into irregular forms. Drips and dribbles of watery paint cascade down the surface, like waterfalls hiding unseen depths behind their shimmering curtain of water. Pulled into the depths of gaseous clouds of paint, we are brought back to the surface with tiny marks that circle and slide, describing the movement of Booth’s hand, blindly feeling for the presence of forms beneath these nebulous surfaces of shifting light.

These circles and dots fall like raindrops across these paintings, sending out shivers of radiant energy. Sometimes they coalesce into subtle grids, sometimes they disperse into asymmetric

constellations, forming flurries of light that dance like fireflies in the night. They are hard edged and soft edged, large and small, with colours that recede and intrude, pulling us into a space that is both transparent and opaque, shimmering with luminous intensity as forms emerge and retreat. So, we stand in a blizzard of colour, as if held in an atomic cloud.

It is easy to see Booth as an abstract painter, playing with the language of colours and forms, as if disconnected from the world. But these paintings are not abstract, they are meta/physical landscapes, manifestations of the invisible rather than imitations of the visible. We stand in snowstorms of paint, mesmerised by waterfalls of light, memories of blizzards and landscapes, but at the same time we are stood gazing at the atomic reality of the world, engulfed in the ocean of atoms that surrounds, penetrates and unites us all. We glimpse objects coalescing into matter, and we see matter dissolve before our eyes. Edges emerge and disappear as space unfolds around and within us, and before we know it, we have become absorbed into the interconnected reality of the world: realising we are only a momentary coagulation in the Being of the Universe.

Booth frequently starts her paintings with a layer of black paint, applying it in dramatic, sometimes brutal strokes - mopped, brushed, thrown - its material substance gripping the surface while pulling our gaze into its dark, intangible depths. Black, the colour of emptiness, a black hole, yet formed from the accumulated, coagulated colours of matter; the swirled,

absorbed mixing together of everything tangible. Black - the colour of the physical world, made from mixing all the colours in the paintbox. But before the paint has dried, while it is still sticky and malleable, Booth will draw veils of white paint across this infinite darkness. They are applied more subtly, a breath of pigment, dripped and dribbled on in a delicate

calligraphy. White the colour of invisible light, the visible manifestation of metaphysical realities, concealing the rainbow in its snow silent emptiness.

-

-

Helen Booth’s work is ice. It is history and time. It is light. It refracts. On canvas, it is a fall caught in motion. Dry oil. It defies.

The very nature of abstraction mirrors the nature of Booth’s paintings; hard to define, limitless. A frame can only contain the pigment, but it is easy to imagine the drips of paint left behind on the wall or floor of her studio after making. Like the water that carves itself a new waterfall, nature, too, is beyond definition, beyond control.

Booth considers the most timeless of subjects - spirituality, and the environment - during the most pressing of times, and this imbalance, this reeling, is reflected in her work. It is both calming and catastrophising. Is it both serene, and screaming. The series is a tightrope walk between the peace and power that Nature herself offers. A play on the untethered.

I was reluctant to use the word spiritual all through my early career, because of the religious connotations that come with it, but now I embrace this word like a tool in my studio. Spirituality is rooted in curiosity, and that is why I paint; to ask questions that lead to more questions. I’m quite happy for my paintings to be seen as spiritual, or for my work to bring a spiritual experience. It means that it’s emotive, powerful and importantly, open. It means that it’s breathing.

I use words like transcendent, mystery, and intangible like I use blues, greys and whites on my canvases. I’ve recently added spiritual to my arsenal in the same way I’ve added pink to my palettes - tentatively.

Booth’s palettes are arresting, layered. They dapple in light, while others cast shadows in their beaded forms. Her use of both traditional and domestic materials leave surfaces tactile, rendering the unpredictability of Nature within their gaps and repeated patterns.

I use mops, buckets of paint, wire wool and sticks to make my marks, and these tools are used during the initial layering. The minute, repetitive marks that I make (during what I refer to as the ‘Autumn’ and ‘Winter’ of my process) are a result of a more contemporary, experimental approach. I use a household baster to drip paint along the top of my larger works, and encourage a stand-back approach, trusting gravity. Then, I use tiny brushes, oil paints, damar varnish and linseed oils to finish.

Over and over and over she goes, raindrops and falling sprays of paint marks on canvas, through hours and days. Booth follows the seasons as she works - chasing the rhythm and pattern of her own influence; the cyclical rhythm of Nature. The changes in time.

We are repetitive creatures living on a repetitive planet in a repetitive universe. Repetition has become part of my own creative language and so my painting in a way, is a process that nurtures this cyclical pattern. The four large paintings, Falls the Shadow, When It Comes, Send Us of the Air and Shadows Hold Their Breath, are a nod to the seasons, the time the Earth takes to travel around the sun and the changes that happen on Earth at a molecular level. I create structure from the initial chaotic surfaces of my work, and this forced pattern is a capture of the human hand. With my work, with the molding and manipulating, shaping and framing, I am ruminating on the need for a human to impose control on the uncontrollable. To make sense of the unpredictable.

So, then, a journey to Iceland, to watch the unpredictable. To be cold, exposed and isolated, with red raw hands on shards of sand and stone. In snowstorms. Rubbing ice into paper. Through blistering wind and calloused coastlines. Gazing out to bits of black rock in the sea that looked just like upright charcoal. Booth, between white snow and black ice, unraveled.

It felt like a ripping apart of sense, for me. I was standing, immersed in this scene of destruction and recreation, watching water that was once ice, thinking about our obligation to save our planet. Thinking about the brutality of Nature and of humanity, and the splitting apart of what should be one entity. How tragic and enormous.

Look at Booth’s small marks on the canvas. These small decisions, made over and over, creating impact on a large scale from repetitive motion, over and over and over.

I’ve always been drawn to these unfathomable topics, but being surrounded by unfathomable beauty and power felt new. Momentous. I had such a tangible reaction to this threatening, dangerous, untouched landscape and it distilled my ideas in an instant.

So, home to Wales, between the heather grey valleys of the Teifi river in March 2020, as the sky emptied of aeroplanes and the hedgerows lay undisturbed by cars.

I was in Iceland for a while, in the quiet, as the news alerts and the worry snowballed, with the rising charts and the days of isolation, counting tolls - this unfathomable virus, counting cases, counting days -

1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 —

And then, when I did eventually get home, and into my studio, I realised that I had never been more determined to get these works out of my head and onto the surface. I almost fell into a creative trance when painting, especially in the later stages. Adding thousands of dots onto the surface of the works, and counting to ten with each group of marks -

7, 8, 9, 10

-before starting again from one. This counting formed a very clear rhythm as I painted, and because of the sheer scale of these works, there are signs of my process all over the surface - this ritual, this repetition. I like to think of them in the same way I think of the serendipitous patterns that are found in a snowflake or on a forest floor.

In the gallery, surrounded by colour and quiet, the paintings loom.

The paintings whisper.

Like the water that falls from the black cliffs of a waterfall’s edge, or the paint that falls to the ground from the canvas -

I want the work to be fallen into.

Booth’s paintings are an ebbing tide. They are contradicting, menacing, inviting. They suggest, that we, too, are ice, or water. That we are history or time. We are light. We refract. We are a dance caught in motion. We are dry oil, a mess, a destruction, a disaster. A miracle. They show that we are beauty, soul and soil. That we are part of a whole. That we are what we surround. That we are marks - thousands of them - shared by a common composition. They whisper, telling us that we defy definition, reasoning, prediction.

They whisper -