Last week, I spent three days in London, and, unexpectedly, the highlight turned out to be the Van Gogh exhibition at the National Gallery.

I’ve always appreciated Van Gogh’s work in the way one might admire a landscape through a train window; glimpses of fields bathed in evening light, beautiful but fleeting, passing too quickly to fully immerse oneself in their depth.

His paintings, monumental and revered, have long seemed to me like a distant kind of brilliance: remarkable, but not deeply personal. Yet something shifted as I walked through The Poetry and Lovers exhibition. I found myself unexpectedly overcome with emotion, standing quietly in front his paintings and drawings.

I love painting.

It’s woven into the fabric of who I am, but rarely does art move me to tears, but from the moment I entered the first indigo-painted room, though, I was a mess of emotions.

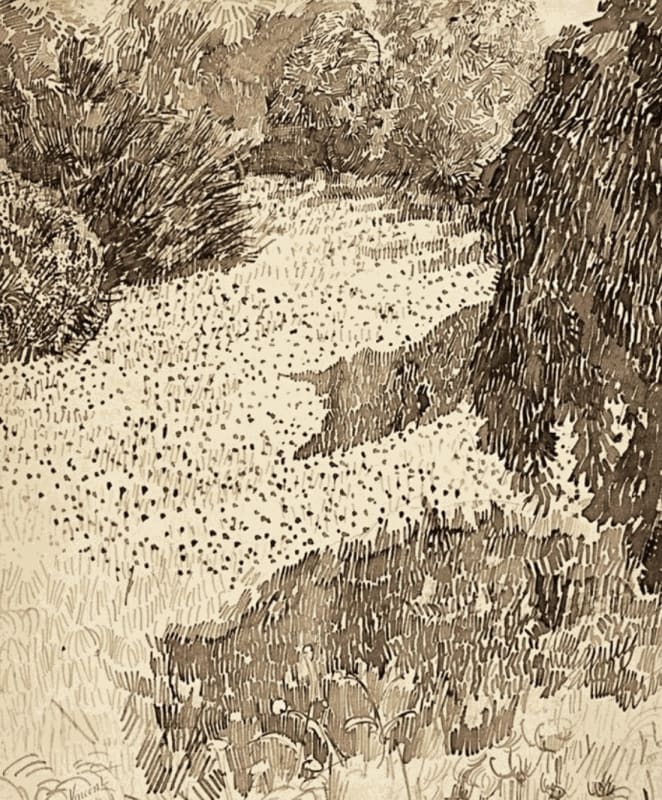

There is something profoundly alive in his ink drawings. His repeated marks, small, deliberate gestures, accumulate into something that seems to breathe. Each stroke feels like a pulse, as though he isn’t merely drawing what he sees but what he senses beneath the surface. His foliage doesn’t sit still; it almost trembles.

The marks are layered so patiently, they seem to hum in place, vibrating slightly in the stillness. I spent a long time absorbing the details - leaves, branches, and fields - all rendered with such rhythm and care. They don’t simply depict; they seem to exist in a realm of their own, caught between presence and memory.

After the exhibition, I went to visit my daughter in North London. She lives two floors up, with a view of treetops stretching out beyond her window. Watching the wind ripple through the leaves, I couldn’t help but see them through Van Gogh’s eyes, the way he captured movement, not as a fixed form but as a living, shifting presence.

Sublime.

And then there are the titles.

Words that seem ordinary at first glance, but, with the shadow of history cast over them, become almost too much to bear. The Asylum at Saint-Rémy, the final years of his life, these contexts, which we now know so well, make the calm beauty of his work even more poignant. What could have been mere moments of solitude were, in truth, scenes drawn from deep suffering. To see such care in the lines, such tenderness amid chaos is quietly heart-breaking.

I left the exhibition feeling not just inspired, but awakened.

I suddenly had the urge to reach for my inks again, to head out into the landscape, to capture something of the movement in leaves and sky, of time caught in repeated marks.

Seeing the exhibition was like opening a door to a different way of seeing.

This experience has also set my mind turning toward Iceland, where I’ll soon immerse myself in the wild, raw landscape once more. There’s something grounding about being surrounded by such vastness, fields of basalt, empty expanses of snow-covered earth and sky.

Perhaps there, with ink in hand, I’ll find a new rhythm, a new language of marks.

Until then, I carry Van Gogh’s vision quietly with me, the movement of ink, the spaces between the strokes, and the intangible pulse of something greater than what’s seen.

I know that the exhibition at the National has only 1 week left, and it is sold out, but I joined as a member and was able to go see the exhibition immediately. If you get the chance then I would highly recommend going to see it. It might well inspire you like it has me!